Burn or Lock up, as Needed: How Famous People Throughout History Have Used Commitment Devices

Stories of famous people and commitment devices, drawn from history.

Why do something today when you can put it off till tomorrow? – the refrain of the akratic

Akrasia has been a bugbear attending the progress of human civilization since the dawn of time. It consistently shows up in ancient works – in Plato's dialogue "Protagoras", for example. In a way, that's reassuring – while modern life has undoubtedly exacerbated the problem, it shows us that akrasia is deeply ingrained in the human psyche.

Of course, we try to combat it – and where that's not possible, we try to hack it. One method that many of us have discovered and rediscovered, through history, is the Commitment Device.

The most famous commitment device you’ll encounter is probably the Ulysses pact, named after the strategy used by Ulysses (or Odysseus, if you prefer the Greek version) to ward off the Sirens, in Homer's Odyssey.

Odysseus passes by the island of the Sirens on his way back home from the Trojan War. The Sirens, of course, are creatures who habitually lure sailors to their doom with sweet songs. Odysseus is curious to hear the fabled music, but he knows that resistance is impossible once he hears its bewitching notes. So he tells his crew to tie him to the ship's mast and plug their own ears with beeswax. This way, he's able to hear the song of the Sirens without being lured into their trap.

As we delve more into history, we see them everywhere. So many significant things have been achieved with the help of commitment devices. Here are 10 examples of famous people who've set up self-binding mechanisms, and the contracts they've sworn by.

Lock Me Up: Relentlessly Remove Distractions

It's no secret that writers are especially prone to akrasia. Staring at that blank sheet of paper and willing the words to come – ugh. No wonder so many writers have resorted to and had success with commitment devices.

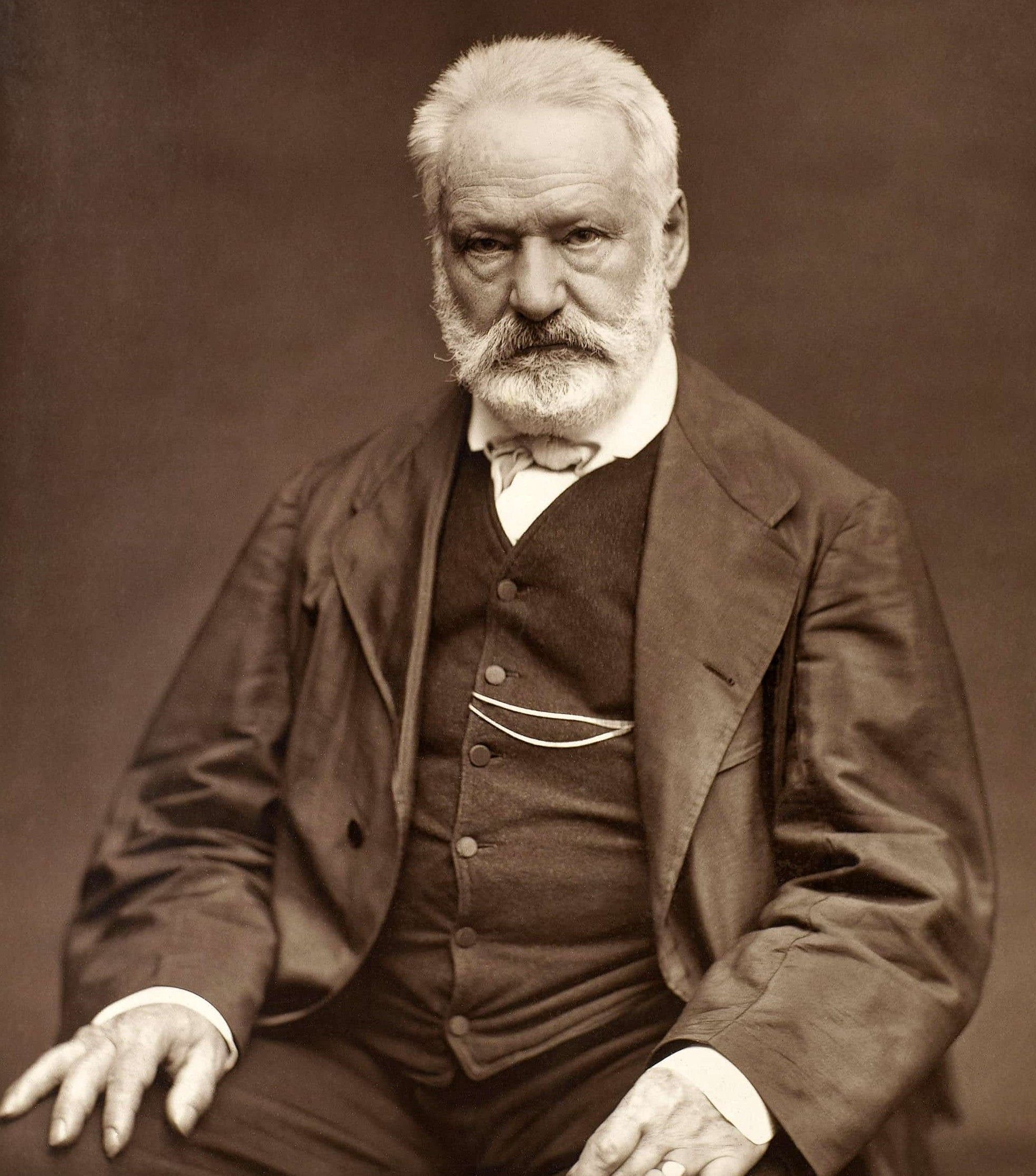

Victor Hugo: Take away my clothes!

One of the greatest French poets and novelists of all time may have not delivered the masterpiece that is The Hunchback of Notre Dame if he'd succumbed to his procrastination. Hugo’s battle with akrasia is well known, as is his unique commitment device to beat it. After months of neglecting work on The Hunchback, which was already commissioned, the writer was given an ultimatum and a deadline of six months to finish the book. To make sure he didn't waste any more time, Hugo gave his aide a critical task – to lock away all his clothes. With nothing to wear, he was less tempted to go out and get distracted. The result? – the book was completed well before time.

Demosthenes: Shave half my head!

Making it impossible to go out appears to be a common trick. (Back then, I suppose, all the distractions were outside the house. We regret to say it's more difficult than that now.)

Plutarch tells the story of Demosthenes the orator (born 384 BCE). Demosthenes of Athens was born to wealthy parents, but upon their death, his guardian swindled him and left the boy practically penniless. With an aim to sue his guardian, Demosthenes decided to train himself in legal rhetoric and study oratory.

He had a few disadvantages as he started his self-imposed routine of learning – a delicate physique and a speech defect, both problems in Ancient Greece, which valued gymnastic prowess and eloquence in speech in oratory. Realizing what it would take to become a great orator, he doubled down, building himself an underground study, and religiously practicing speaking before a large mirror.

In Parallel Lives, Plutarch tells us of the interesting commitment device Demosthenes employed: he shaved half his head to force himself to stay indoors, to continue studying.

The commitment device seems to have worked – Demosthenes soon became known as the greatest of ancient Greek orators, who roused Athens to oppose both Philip of Macedonia and his son Alexander the Great.

Douglas Adams: Locked without a key

“I love deadlines…I like the whooshing sound they make as they go by.”

This quote by Douglas Adams, author of The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy, sums up his lifestyle. A self-confessed chronic procrastinator, Adams did many things to avoid – well, having to work. He’d take long baths conjuring up entire plots – only to forget them while getting dressed, “forcing” him to go back into the tub. He'd go on writers’ retreats to avoid socializing – but would make friends with his hosts and spend all his time drinking with them.

Finally, either he or his exasperated publishers decided drastic measures were needed, and Adams was promptly locked in a room with only a typewriter. Apparently, some publishers would even lock themselves in the room and glare at him till he finished his book. No greater motivation than a stern pair of eyes, it seems!

Jerry Pournelle: Living like a monk

Science fiction writer Jerry Pournelle was the first person to ever produce an entire novel on a computer. An impressive feat, but what's more impressive is how hard the author of The Mercenary worked to not let new-age technologies consume and distract him from his work.

Unlike Adams, Pournelle was not compelled by his publishers to find a distraction-free space. He made himself one – his “monk cell”, which he first spoke about in a magazine column in the 1990s. He described it as a space with limited power, a PC with only writing software, and no other gadgets. He’d write, stretch, and exercise, then write again till he was done.

Our takeaway? Don't waste willpower – just remove the ability to get distracted.

JK Rowling: Bye to Distractions

Living like a monk does not mean you completely give up the small pleasures of life. After all, JK Rowling achieved the goal of a distraction-free work atmosphere by moving into a 5-star hotel.

While you may or may not be a fan, we have to admit that the Harry Potter series was a huge accomplishment – and a lot of work. According to Rowling herself, there were times when it almost didn’t happen. She admits to giving in to distractions, both external, like chores, or internal, like mulling over the perfect font, letter size, and line space, before actually writing anything.

Writing the last book in the Potter series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, JK Rowling admits, was a struggle.

“As I was finishing Deathly Hallows there came a day where the window cleaner came, the kids were at home, the dogs were barking,” Rowling recalled in an interview. But with the book's deadline looming, she knew too much was at stake to risk non-productive days. She decided to try something a little novel and extreme – moving into a suite at the Balmoral Hotel in Edinburgh.

In Cal Newport's Deep Work, the author refers to this trick as a "Grand Gesture." He writes, "The concept is simple: By leveraging a radical change to your normal environment, coupled perhaps with a significant investment of effort or money, all dedicated toward supporting a deep work task, you increase the perceived importance of the task. This boost in importance reduces your mind’s instinct to procrastinate and delivers an injection of motivation and energy."

The common thread that runs through these examples is that sometimes, you can only get work done by making it physically impossible to leave your desk. Add some external threats and a dash of pettiness for extra taste.

Cross the Rubicon and Burn Your Ships: Deliberately Remove Options

We think of optionality as a blessing, but it could be a curse.

Picture someone who's on a sabbatical from their comfy, tried-and-tested job, in order to dip their toes into a new career. They might view the old job as a safety net. "Hey, if this doesn't pan out, my old desk is just where I left it." But that safety net, snug and reassuring as it is, might be the very thing that holds them back, preventing them from throwing themselves headlong into their new adventure, and giving the new career everything they've got.

And surprise surprise, ultimately, they get nowhere.

When the knowledge that other options exist is preventing us from giving our all to one chosen course of action, optionality might be holding us back.

By deliberately removing the options (quit altogether, instead of taking a sabbatical!) you're committing, doubling down, on one path. The stakes have suddenly got higher. Your back is against the wall. Your motivation soars.

Here are two historical examples of this principle executed.

Julius Caesar: Crossing the Rubicon

If you’ve ever heard the phrases “crossing the Rubicon” or “passing a point of no return”, we have Julius Caesar to thank for them. The Roman general has given the world one of the oldest examples of a commitment device – specifically, committing to one path, and removing options.

Caesar was the governor of Cisalpine Gaul, a Roman province separated from Italy proper by the river Rubicon. The law at the time was clear – no commander could enter Italy with their army. But Caesar had other ideas, and in 49 BCE he led his army across the Rubicon and into Italy – effectively starting a civil war. Crossing the river was Caesar’s commitment device – he knew once he did so, there was no going back. He had to fight and win the war or perish. And here’s the lesson he’s taught the world: sometimes you have to make a commitment you can’t take back. By committing to a decision, you're deliberately taking away choices.

We highly recommend loudly yelling "Alea Iacta Est" ("The die is cast!") when you cross your own Rubicon. Trust us, it works.

Hernán Cortés: Burn the ships!

In 1519, the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés decided to make a bid for Aztec gold, taking 700 soldiers and sailors aboard 11 ships from Spain to the erstwhile empire. But as they approached, he realized they were greatly outnumbered. His men, terrified and demoralized, tried to take away a few ships to escape to safety. But Cortés was having none of it – he ordered his own ships to be sunk and announced that they would only go home on Aztec ships. Cortés’ strategy worked – his men were left with no choice but to commit to the fight.

The lesson this extreme tale provides? It's certainly a risky strategy, and to be used with caution – but sometimes, you really have to leave yourself without a safety buffer to make sure you move forward.

A Looming Threat: Introduce Real-World Consequences

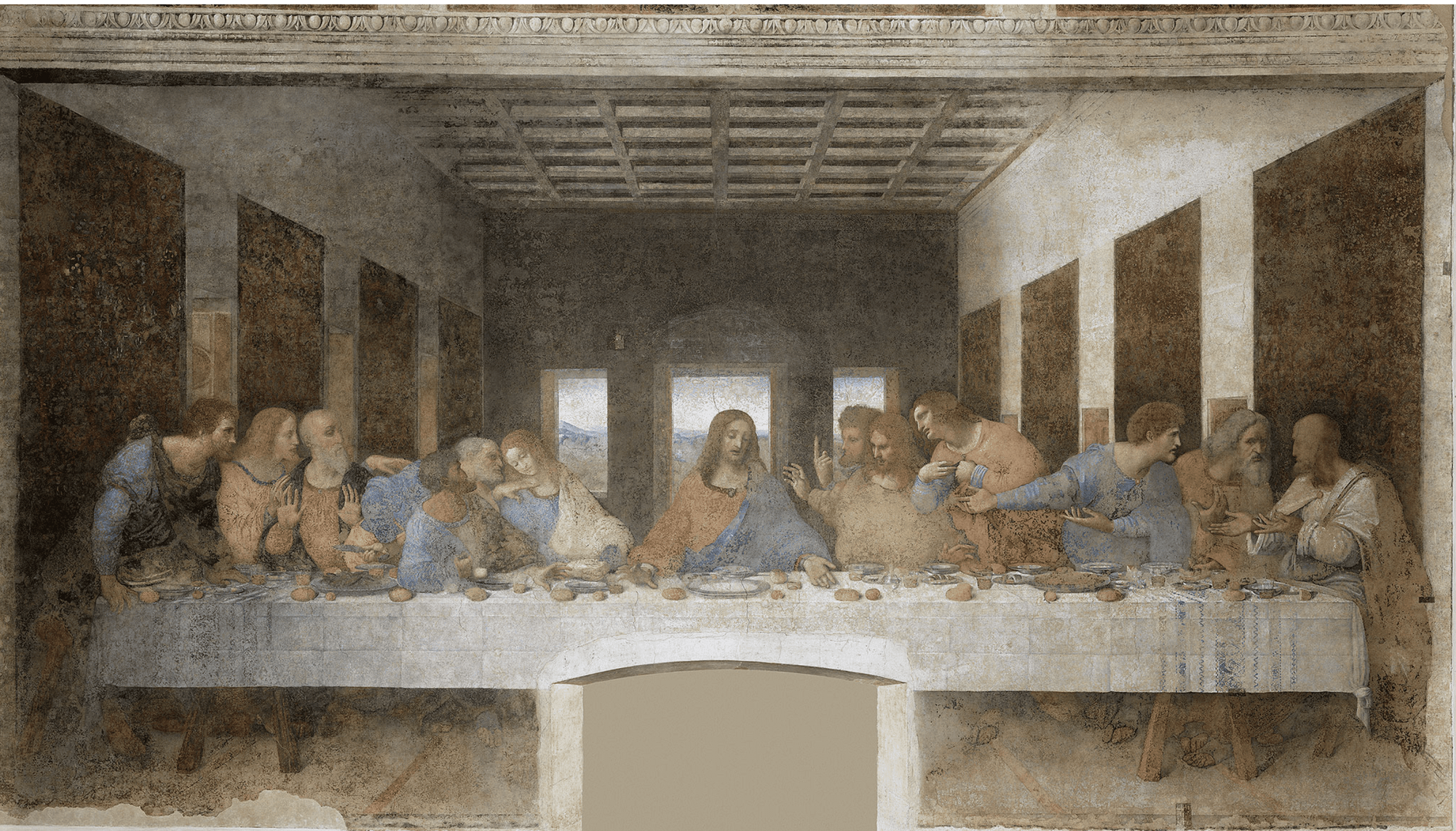

Leonardo da Vinci: External Threats Work

The Italian Renaissance man was a famed daydreamer who never actually finished anything on time. His genius often got in his way – he wanted to explore everything that caught his fancy, and every new shiny thing in science and art sent him down a rabbit hole. This led to him constantly wasting energy and abandoning projects (some of which are still being figured out).

Da Vinci's The Last Supper, a notable example of his use of a commitment device, was completed in just three years, a surprise considering his other projects typically took at least a decade and a half. Apparently, da Vinci only sped up work when his patron, Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, threatened to cut off funds. That, plus a jabbing taunt from a church prior (in return, Leonardo threatened to use his likeliness for the face of Judas) led to da Vinci doubling down to focus on his work.

External nudges often work great as commitment devices, as da Vinci would testify.

Stephen King: Create Your Own External Threat

When you don't have a patron breathing down your neck (which can, counterintuitively be a good thing – hey, we built an entire product around this!) you can create that external pressure for yourself.

In the introduction to The Green Mile, the master of horror writing, Stephen King, explains how the story came to be. Struggling with insomnia, King would often think up entire stories as he waited to fall asleep. He'd compose prose in his head, much as he would on a word processor, each day getting a bit farther. That's how The Green Mile was originally conceived. King liked the idea, but ultimately, it came to naught, and he pursued other stories.

Then he got a call from his foreign rights agent, who had been talking with a British publisher about the serial novel format – originally popularized by Charles Dickens, but something that had fallen out of fashion.

In the words of King himself – "Man, I leaped at it. I understood at once that if I agreed to such a project, I would have to finish The Green Mile. So, feeling like a Roman soldier setting fire to the bridge across the Rubicon, I called Ralph and asked him to make the deal. He did, and the rest you know."

External accountability – a most powerful commitment device! With the pressure of not just a publisher but also the public waiting for him to complete it, writing The Green Mile got much easier afterward!

Alice Wu: Strength of Emotions

Have no way of introducing an external threat? Keep it simple, and make a commitment to write a check to someone or something you hate.

Asian-American filmmaker directed her second film, The Half Of It, more than 15 years after her debut, Saving Face (both available to stream). Both films had a lot of strong emotions attached to Wu as a person of color and a member of the LGBTQ+ community, so she struggled with writing The Half Of It after her long time away from Hollywood. Her solution to get it done was unique – she wrote a cheque to an organization she hated on principle, and told her friend to send it in if she didn’t finish writing the movie in five weeks.

You can do this yourself with tools like Stickk – set up an anticharity (a football club you don't support? a cause you don't agree with?) who will be the recipient of your money if you fail!

Final Thoughts

For us, the best part of peeking into the lives of the greats and witnessing their battles with akrasia is just a feeling of kinship in their struggles. These stories aren't just entertaining anecdotes, they're proof that the struggle with procrastination and distraction is as old as time and as common as the air we breathe.

But here's the kicker: if these giants of history, literature, and art could find creative, sometimes downright bizarre ways to overcome their tendency to delay, what's stopping us? You don't need to start burning ships or locking away your clothes (though if you do, let us know!). The essence here is about finding what works for you, whether it's setting up digital blockers, making a pact with a friend, or simply turning off your phone and getting down to business.

Akrasia is not a personal failing, it's a universal challenge. And commitment devices can be as unique as the individuals who employ them. It's time to make your move, embrace your own brand of commitment device, and perhaps, write your own history.

Want to read more?

- Try a Commitment Device to help you get work done

- Beeminder Integration is Here! - Use BaaS + Beeminder Together!